Weaving Memoir and Sociology in Harlem

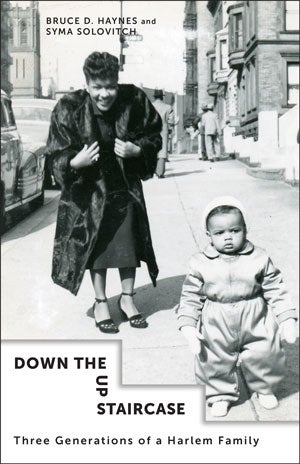

Down the Up Staircase: Three Generations of a Harlem Family

A new book by Bruce D. Haynes, UC Davis professor of sociology, and his wife, writer and educator Syma Solovitch, chronicles the journey of Haynes’ Harlem family through three generations, connecting their journey to the larger historical and social forces that shaped and transformed Harlem and New York City across the 20th century.

Down the Up Staircase: Three Generations of a Harlem Family weaves memoir and sociology to document the shifting fortunes of the black middle-class family, and of Harlem itself, and illuminate the tenuous nature of status and success among the black middle class. Using a micro-macro perspective, the authors unpeel the sociological layers that weighed on every step of the family’s journey, demonstrating that not all “middle classes” are the same: Among blacks, middle-class status may provide a buffer from poverty, but it rarely brings economic security; race and segregation ultimately limit the value of social and cultural capital among the black middle class.

Haynes, an authority on race and urban communities, was initially reluctant to write the book, the most difficult of all his writings. “Telling the story meant bringing up a lot of pain and exposing it to the world. But I didn’t want to write a book that would sit on a shelf — I wanted to have a book that would illustrate sociology, and show that people make choices but within constraints not of their choosing.”

His wife and co-author convinced him to tell the story. She was the observant outsider-insider who could persuade him to tell the parts that needed to be told. “Without Syma,” he said, “there is no way I could have written the book, or would have written the book.”

In a media interview, Solovitch described a particular line that Haynes fought against including. It comes early on, when the authors describe the state of the family home, a 5,000-square-foot limestone mansion in fashionable Sugar Hill in Harlem. The book excerpt follows:

By 1995, my parents were living like squatters in their own house. The pipes were frozen and busted, the roof was beyond repair. … Nothing had been dusted, cleared, discarded or repaired in more than two decades. What was once a formal parlor that hosted W.E.B. Du Bois and other Talented Tenth elites now held the remnants of my brother George’s failed business ventures. Half-empty cans of spray paint, battered furniture and broken appliances heaped on top of one another. … One might have taken the scene for the final stages of a family move — all stacked up and ready to go — except that there was a frozenness about it, a sense of havoc in suspension.

“I wanted to begin with talking about the house,” said Solovitch, who did not make it past the entryway during the first 18 months of their relationship. Although she had often accompanied Haynes when he visited his parents, his mother — an elegant and proud woman — was too embarrassed by the deterioration of the house. Once they became formally engaged, his mother resigned, telling Solovitch, “Well, I guess you have to see it now.”

Although Solovitch felt well prepared for what followed, “It was beyond my imagination.”

In writing the book, Solovitch said of her husband, “Getting him to even see how bad it was, was a challenge.”

What Haynes saw in looking at his life and family’s life, was that even though his family had done much to achieve the great American dream, this didn’t secure or assure success for their offspring.

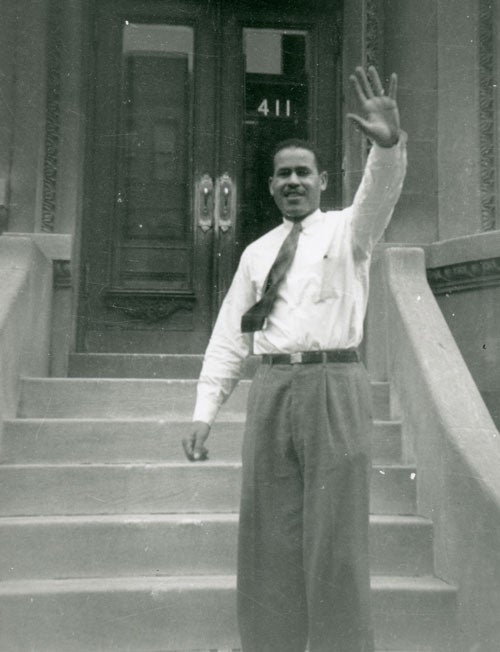

Descendants of slaves, Haynes’ ancestors owned property in the South. His grandfather George Edmund Haynes was the founder of the National Urban League and the first African American to earn a doctorate from Columbia University; his grandmother Elizabeth Ross Haynes was a children’s author of the Harlem Renaissance and prominent social scientist.

REVIEWS

- “Excavating an African American Family’s Past in a Townhouse in Harlem” (The New York Times, May 11, 2017)

- “Tracing His Family’s Migration From the Rural South to the Big Cities of the North” (The Washington Post, May 12, 2017)

Both of his parents had master’s degrees and had professional careers. He and his brothers attended elite private schools.

Yet, he asks in the book, “How much protection did the gains of my forefathers, the safety net of a stable, two-parent household, and the advantages of expensive private schools ultimately keep my brothers and me from becoming three more black male statistics?”

As the book jacket describes, Down the Up Staircase is a portrait of a family “walking a tightrope, one misstep from free fall.”

Portions of this story are based on quotes taken from media interviews, including two on radio: KDVS, with Andy Jones, UC Davis lecturer; and Capitol Public Radio’s Insight, with Beth Ruyak.

Karen Nikos-Rose is a senior public information representative in the Office of Strategic Communications.