Editor's note: After a 16-year "holiday," UC Retirement Plan members will once again start contributing to the plan in July, by order of the Board of Regents. The board decided in March that renewed contributions were a must for the financial health of the plan. "The longer we wait to restart contributions," UC spokesman Paul Schwartz said, "the bigger the financial deficit UC and its employees will need to fund." This article from UC Berkeley's faculty-staff newspaper explores the controversy over the plan's finances.

Early this year, in an Associated Press report on looming retirement benefits issues nationwide, a prominent equity-market analyst predicted that coming discussions around both pensions and retiree health care coverage will be "lively, political and complex."

Late last month the University of California and its employees joined that consequential exchange, as UC and three of its largest unions began their first formal negotiations on a watershed change to the system's retirement benefits equation.

The subject of their conversation is UC's plan to restart contributions to the UC Retirement Plan — the $42 billion defined-benefit pension fund for the UC system's current and future retirees — for the first time since 1990.

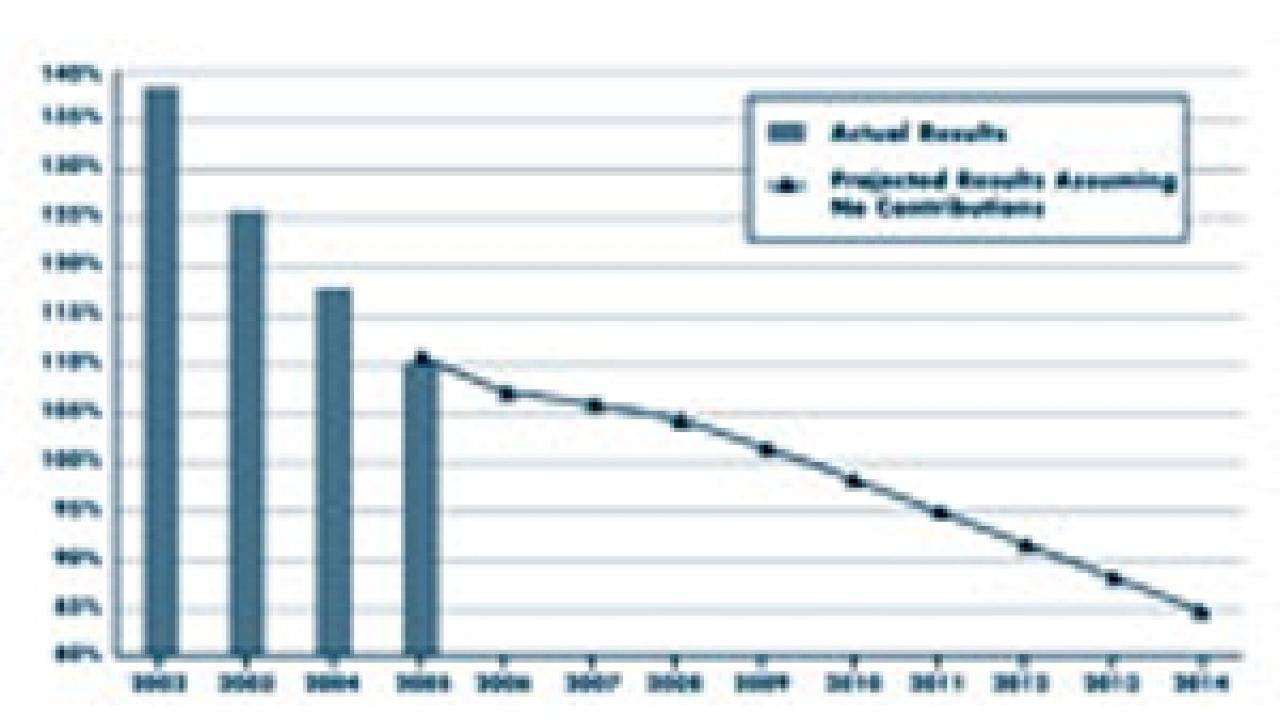

Based on their analysis, the regents and UC administrators insist that contributions from both employees and the university — together equaling 16 percent of covered earnings by 2014 — are necessary, beginning in July 2007. The change is required, they say, to prevent further erosion of the UCRP's funded ratio (fund assets divided by present and future obligations) so that it can keep its promises to current and future retirees.

To make its proposal fly, UC will need money from the state (and perhaps other sources) to cover its yet-to-be-determined portion of the contribution, to be sure. But it also must negotiate with UC unions, which together represent 65,000 employees, to secure their agreement on whether, when, and how much their members will contribute to the plan. (For nonrepresented employees, numbering about 105,000, the university sets the terms of the contribution.)

Labor's buy-in will not be an easy sell.

Critics of the plan raise a number of questions and concerns about the proposed employee contribution: How wisely has the retirement fund been managed in recent years, and why the troubling erosion of its once impressive surplus? Is there sufficient sunshine and public input on critical decisions affecting the UCRP?

Are contributions in fact necessary as soon as next year to keep the UCRP solvent? If they are necessary, what is the appropriate split between UC and employees? Why not return to the formula in effect before the contribution "holiday," between 1976 and 1990 (when employees contributed, in any given year, 1.7 percent to 3 percent of covered pay, and UC added 4 percent to 16 percent)?

What further benefits cuts may be on the horizon? If employees start paying into the pension fund, what guarantee is there of pay raises adequate to cover the additional costs?

Though the unions are taking a lead role in articulating such questions, their concerns are shared by many nonrepresented employees and faculty.

Professional actuaries, as in the national debate on the future of Social Security, disagree on the retirement fund's long-term prognosis. UC's most vocal critics accuse the regents of mismanaging the UCRP.

Berkeley staff member Jim Stockinger does double duty as a childcare worker (making him a member of the Coalition of University Employees) and a sociology lecturer (thus his membership in the American Federation of Teachers' branch for UC lecturers and librarians). He said the past year's executive compensation controversy has "seriously undermined" UC management's credibility.

Davis lecturer weighs in

Kevin Roddy, a UC Davis lecturer and an AFT officer, said: "The question of accountability has been festering for years." But the "recent scandals," he added, have made that issue "more pernicious" than ever.

Faith Raider, a researcher for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, echoed the theme: "Workers' trust level in UC management is at an all-time low. So when workers learned that UC was saying the plan needs to be funded (by employee contributions), their reaction was, 'Let's look at this ourselves; we don't trust what they say to us anymore.'"

One Berkeley employee who has steeped himself in these issues is Paul Brooks, a spectroscopist at the College of Natural Resources and a bargainer for the University Professional and Technical Employees. A 27-year UC employee, Brooks began tracking UCRP's fortunes in the early 1990s, he said, and has stepped up his background reading and numbers-crunching since first getting wind of the contribution plan.

"Everyone wants to make sure that the pension fund stays solvent. But we need to get better oversight and management and determine whether the contribution is necessary or not."

He said he is troubled by policy decisions that he believes have weakened the UCRP. On the liabilities side of the ledger, he points to the wave of early-retirement incentive programs, known as VERIPs, in the early '90s, which increased the number of retirees drawing from the pension fund and, for most who signed on, the number of years they would enjoy those benefits.

How the UCRP's assets are being managed is another area of concern for Brooks. In the past, the lion's share of those assets was managed internally, and the costs of doing so were "minuscule," said former UC Treasurer Patricia Small (Kellett), now a private investment manager in Marin County. Today, private firms are paid to do much of that work.

"If the fund has $40 billion and there's a 0.5 percent commission," Brooks calculated, "that's $200 million a year; if the commission is 1 percent, it's $400 million."

The unions recently forwarded to UC a number of requests for information on the pension fund; one question that Brooks would like answered is how much its external managers are being paid.

Management change

Following threads of UCRP history back in time, he is even more deeply disturbed by decisions in 2000 to change the financial management of the fund, "which was one of the most successful in the U.S. up to that time. Why on earth was that done?" he asked.

In fact, the fund's management was not the only thing that changed in 2000. The university also changed the overall investment philosophy, as adopted by the Board of Regents and executed by the treasurer's office.

For many years, UC's investments were managed by an in-house staff, focusing on a group of carefully screened, mostly large-cap U.S. stocks. Under the direction of three successive treasurers, the last of whom was Small (1995-2000), returns were robust enough to keep UCRP fully funded and then some, in marked contrast to most other public-pension funds.

"The returns over that time period were above average versus the toughest and highest-quality benchmarks in existence and versus our peers," Small said.

Then, in 1999, the regents called for a review of the treasurer's office. Selecting Wilshire Associates as their consultant, they charged the firm with "(making) recommendations about the treasurer's overall investment approach," Small said.

Wilshire recommended that UC diversify its investment portfolio, primarily by reducing its exposure to blue-chip U.S. stocks; increase its exposure in private-equity arrangements; and add non-U.S. equities to the mix — and that it accomplish this by shifting billions of dollars to index funds managed by outside firms.

The shift to index funds has attracted much criticism, particularly as overall investment returns have returned to single-digit levels since the end of the market boom of the late '90s. Index funds are "passively managed," in that they attempt to mimic the makeup of entire indices such as the Standard & Poor's 500 or the Russell 3000; their selling point is that they essentially guarantee investors that they will do no worse than the overall market. Critics point out the converse: Index investors also do no better than the market.

Treasurer Small, at the January 2000 meeting of the investment committee, said "studies show that diversification for its own sake serves to dilute returns over the long term." If, between 1989 and 1999, she calculated, the UCRP's assets had been passively invested in this manner, "the fund's return would have been lower by 127 basis points per year," translating to a $5.2 billion loss over that time period.

The UC treasurer's office responded that it cannot comment on Small's claim because "it is unclear what passive asset allocation she is using."

Despite these arguments, the regents adopted Wilshire's recommendations, contained in a 30-page Investment Strategy Study dated March 16, 2000. These included changing the treasurer's reporting arrangement, from the regents directly to UC Office of the President; revising the successful asset-allocation model that Small and her staff had followed (in part, it was later explained by Regent Judith Hopkinson in a meeting with a group of UC employees, "to decrease risk and volatility while enhancing returns"); and moving $8 billion in equity investments into index funds managed by commercial investment-management groups.

Wilshire's role expanded by the next regents meeting, in May 2000, when it was hired for a three-year run as a general consultant to the Investment Advisory Committee, to provide ongoing financial advice and to "assist in implementing" its own asset-allocation recommendations to the regents.

Treasurer Small retired soon thereafter. She declined to discuss publicly the circumstances of her departure.

In 2002, the treasurer's office equity investment staff was laid off, and management of the $15 billion it had overseen was outsourced to several dozen private-sector investment managers. Left in-house, for the time being, was the fixed-income portion of the UCRP portfolio, although in November 2005 some $8 billion of those assets were also transferred to external managers.

Watchdogging the regents

Charles Schwartz, an emeritus professor of physics at Berkeley, and a longtime observer and critic of the regents, said his analysis of financial reports showed that more than half of the 40 external fund managers responsible for UC's investments "failed to perform at the level of their assigned benchmarks" between June 2005 and June 2006.

In the absence of other historical and financial data (a great deal of which, Schwartz said, he has requested over the years to no avail), he concluded that subpar performance by UC's external investment managers is at least partially to blame for the UCRP's declining surplus.

In response, the UC treasurer's office stated that Schwartz had requested and received all peer group comparison information maintained by the treasurer. The last delivery of records occurred Oct. 20, according to the treasurer's office. That was six days before the Berkeleyan published this article. As of Nov. 6, the treasurer's office reported that it had no outstanding California Records Act requests for comparative data on the office's investment performance.

The treasurer's office also had this to say: "In terms of external managers, 18 outperformed their benchmark and 22 underperformed their benchmark for the one-year period ended June 30, 2006. While it would be ideal for all managers to outperform their benchmarks for every time period, underperformance of this nature during relatively short periods such as this is not unexpected. The office manages the portfolio for the long term and according to risk parameters determined by the regents' Committee on Investments. The results experienced this fiscal year are unfortunate, but not outside the regents' tolerance for risk. The office continues to monitor all external managers and are not anticipating making changes based on performance over this time period. Please note that overall, the UCRP outperformed its benchmark by 26 basis points over this period."

How do the regents and the UCRP's fiduciary stewards account for the shrinking funded ratio? In part because of the secrecy in which minutes of closed meetings and other key documents are held, the Berkeleyan has been unable to determine, from the university's perspective, why the diminished performance of the past several years has negatively affected the regents' stated goal at the beginning of that decline: the preservation of "the plan's envious level of assets in relation to liabilities."

The more modest goals enunciated in the UCRP's current Investment Policy Statement, dated May 2, 2006, are "to maximize return within reasonable and prudent levels of risk" and "to preserve the real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) purchasing power of assets," among others; no mention is made of the funded ratio whose erosion has prompted the call to restart contributions.

Berkeleyan Editor Jonathan King collaborated on the research for this article.

Media Resources

Clifton B. Parker, Dateline, (530) 752-1932, cparker@ucdavis.edu