Quick Summary

- Up to 41 percent of smog-forming NOx emissions in state comes from agricultural soils in the Central Valley

- Rural farming communities most affected

- Potential solutions include precision agriculture, slow-release fertilizers

- Work underway to reduce nitrate in groundwater could also help reduce NOx emissions

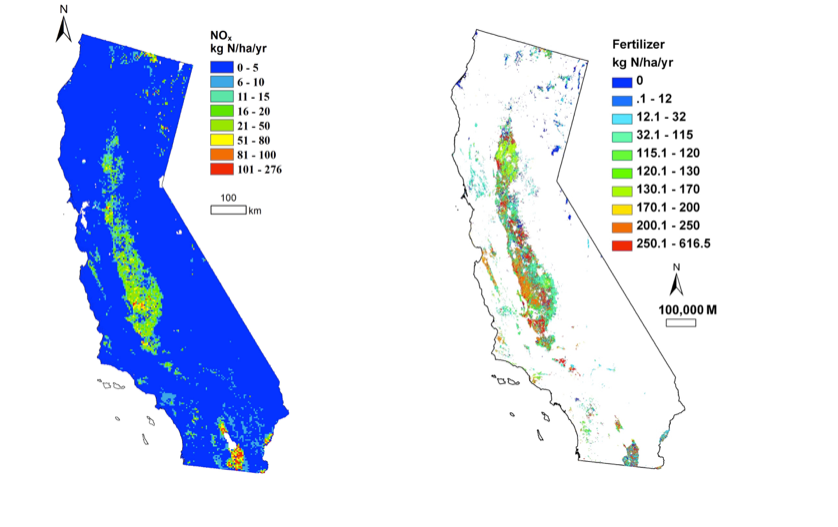

A previously unrecognized source of nitrogen oxide is contributing between 25 and 41 percent of the NOx emissions in California, according to a study led by the University of California, Davis. The peer-reviewed study traces the emissions to fertilized soils in the Central Valley region.

The production of NOx is a natural microbial process occurring in all soils but can increase if too much nitrogen is applied.

In the study, published Jan. 31 in the journal Science Advances, the authors compared computer models with estimates collected from scientific flights over the San Joaquin Valley. Both the model and flight data suggested that 20 to 32 percent of NOx emissions comes from soils with heavy nitrogen fertilizer applications, while NOx emissions from natural soils account for 5 to 9 percent. These emissions are variable, and not a constant presence in the atmosphere.

Rural smog source

Smog-forming nitrogen oxides, or NOx, are a family of air-polluting chemical compounds. They are central to the formation of ground-level ozone and contribute to adverse health effects, such as heart disease, asthma and other respiratory issues. NOx is a primary component of air pollution, which the World Health Organization estimates causes 1 in 8 deaths worldwide.

Fossil fuels have long been recognized as a major contributor to NOx pollution. Technologies like the catalytic converter have helped greatly reduce NOx emitted from vehicles in urban areas. But some of the state’s worst air quality problems are now in rural areas, particularly the Central Valley region, which is home to some of the poorest communities in California.

More food, less pollution

The Central Valley is also one of the world’s most highly productive agricultural areas. Roughly half of the fruits and nuts produced in the United States are grown there. This includes nearly all the nation’s almonds, walnuts, raisins, avocados and tomatoes.

If farmland in California were converted to other uses, such as housing, scientists estimate that greenhouse gas emissions from that land would be 70 times greater. Conserving farmland is an approach to mitigate NOx and harmful greenhouse gas emissions.

“We need to increase the food we’re making,” said lead author Maya Almaraz, a National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellow in UC Davis Professor Ben Houlton’s lab. “We need to do it on the land we have. But we need to do it using improved techniques.”

Potential solutions

The study suggests potential solutions for reducing NOx soil emissions, primarily through different forms of fertilizer management.

Both farmers and the environment benefit when only the amount of expensive fertilizer needed is applied to increase crop quality and yield. Dozens of UC Davis researchers collaborate with California farmers to find the right rate, timing, amount and application of nitrogen to support crop productivity and environmental health.

Finding that perfect balance is tricky because every crop has different nutrient needs, and even those requirements vary based on factors such as soil type, weather, irrigation and how much nitrogen crops can access. Only about half of the nitrogen fertilizer applied to crops is typically used by the plant.

But slow-release fertilizers that deliver nutrients in a way that more closely mimics nature have been shown to greatly improve nitrogen use efficiency of crops, reducing emissions of nitrogen in the environment.

Healthy soils programs that restore carbon in the soil can also help fight climate change and are likely to increase nutrient retention and cycling to crops.

And precision agriculture practices help improve water and fertilizer efficiencies, particularly in perennial crops, such as almonds and grapes.

More solutions are provided by the UC Davis CA&ES.

Building upon work in motion

Two trends already underway in California have been shown to reduce NOx emissions from farmlands: conversion to perennial crops, and efficient micro-irrigation technologies.

For example, William Horwath, a professor with the Department of Land, Air and Water Resources at UC Davis and the J.G. Boswell Endowed Chair in Soil Science, has shown that drip irrigation can produce about 30 percent greater tomato yields with similar amounts of water and nitrogen fertilizer; this also reduces nitrous oxide emissions dramatically compared to flood irrigation practices. Today, more than 90 percent of tomato growers use drip irrigation and, consequently, have significantly reduced NOx emissions. Drip irrigation can provide similar yield and environmental benefits with corn, lettuce, alfalfa and other crops.

The state also began a program this year in which growers work in coalitions to gather information on efficient uses of nitrogen so they can evaluate how and where the state needs to manage nitrogen in agricultural areas. This work aims to reduce nitrate in the groundwater, but it may have a double benefit in reducing NOx emissions.

“Since this source of NOx can remain local, largely in rural farming communities, we need to develop a kind of ‘catalytic converter’ for soils and farms,” said senior author Houlton, a professor with the UC Davis Department of Land, Air and Water Resources, and director of the John Muir Institute of the Environment. “It’s critical that new policies focus on incentives to bring the latest nutrient management technologies to farms so that growers can produce food more efficiently, increasing their bottom line and improving rural health.”

Additional co-authors include Justin Trousdell, Stephen Conley and Ian Faloona from the UC Davis Department of Land, Air and Water Resources; Edith Bai from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Northeast Normal University in China; and Chao Wang, also from Northeast Normal University.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation, Major State Basic Research Development Program of China, Dave and Lucile Packard Foundation, California Agricultural Experiment Station, Bay Area Air Quality Management District and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

This article was updated February 8, 2018, to provide further information about the issue and solutions regarding nitrogen oxide emissions.

Media Resources

Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-750-9195, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu