In September, the Nigerian government made an important change to its food fortification program to date — a set of standards outlining that voluntarily fortified bouillon cubes must contain minimum amounts of four micronutrients: iron, zinc, folic acid and vitamin B12. While some foods are already fortified in the country, the dehydrated seasoning blocks, consumed in virtually all Nigerian households, may prove to be the ideal vessel for some vitamins and minerals.

UC Davis nutritionists and economists played a key role in identifying bouillon cubes as a potential solution for malnutrition in West Africa. They worked together with researchers and program implementers in West Africa to understand the extent of micronutrient deficiency across several countries and estimate how fortifying bouillon cubes could reduce deficiencies and save lives. Their work suggests that fortifying the cubes is a cost-effective, equitable way to incorporate scarce micronutrients into daily diets, with a widespread impact on health outcomes.

“We hope that by being able to provide some evidence on what the potential impacts of bouillon fortification are, that discussions will be better informed and result in policies that are going to be effective at reducing deficiencies,” said Reina Engle-Stone, a UC Davis associate professor of nutrition.

Essential vitamins and minerals

Compared to fat, protein and carbohydrates, we need micronutrients in lesser quantities. But they are no less essential to our bodies. In West African countries, five vitamins and minerals have high rates of deficiency: iron, zinc, vitamin A, folate and vitamin B12. Though deficiencies may not be visible — micronutrient deficiencies are often called “hidden hunger” — they can be dire; neural tube defects in the womb, which are more likely among mothers with inadequate folate, can result in infant deaths.

Diets in this region tend to lack the best sources of these nutrients due to factors such as food insecurity and lower socioeconomic status. Jennie Davis, a UC Davis postdoctoral scholar in nutrition, interviewed Ghanaian households to understand food consumption patterns as part of the project. A typical days’ meals often include a spiced breakfast porridge of millet and sorghum, followed by an evening meal of soup served with a dough of cassava and corn flour called tuo zaafi. Meals are scarce in animal products, which are rich in the missing nutrients but are more expensive than grains and tubers.

In addition to lack of access to micronutrient-rich foods, infections further compromise nutrient absorption. Where clean water is harder to come by, illness is more widespread, leading to stomach symptoms that reduce how much nutrition people can get from their food. “In places where people are exposed to a lot of different infections, that can interact with nutritional status,” said Engle-Stone.

Finding foods to fortify

For decades, researchers, governments and humanitarian organizations have searched for low-cost interventions to stave off the health impacts and mortality caused by these deficiencies. Some staple foods, including flour and cooking oil, are already fortified, but malnutrition persists.

About 15 years ago, Engle-Stone worked with collaborators at the nonprofit Helen Keller International in Cameroon to identify foods that are most widely consumed — and therefore would have the greatest potential impact when fortified. In surveys of household consumption, one product stood out: bouillon cubes. “Of all the foods that they were considering putting micronutrients in, this was the one consumed by almost everybody,” said Engle-Stone.

Additional survey research found that virtually all households in Nigeria consumed bouillon cubes, as well as more than 80 percent of households in Senegal and Burkina Faso. After water and salt, it’s the third most consumed product across urban and rural areas. The cubes, a mix of evaporated seasonings and salt, are added to soups and stews for flavor.

Still, interest in fortifying bouillon was initially lukewarm. Bouillon is more than 50 percent salt. With sodium levels already high in West Africa, there was concern that fortifying bouillon would lead to even greater sodium intake.

But recent research has found that bouillon is a lesser source of salt than thought. Based on reports of what food products Ghanaian households purchased and how often, Davis calculated daily salt consumption. She found that while salt consumption was indeed high, bouillon contributed less than a quarter of total salt intake. “It’s a relatively small player in conveying sodium,” said Stephen Vosti, associate adjunct professor emeritus of agriculture and resource economics. “While bouillon surely has a place in any national sodium reduction program, it could be a very important vehicle for delivering micronutrients.”

Packing nutrients into cubes

Seeing the potential in fortifying bouillon, the Gates Foundation contacted UC Davis researchers in 2019 to investigate its ability to deliver micronutrients. While the cubes seemed a promising target for fortification, questions remained.

First, could food scientists pack all five micronutrients together into a cube? Researchers worried that while cubes were great in theory, adding the micronutrients could prove troublesome. Some nutrient compounds chemically react with others, creating undesirable colors, tastes and odors. The team partnered with a consortium of researchers and industry representatives to develop a test cube, ultimately produced by the Spanish food producer Gallina Blanca Foods. “To everybody’s surprise, it actually, technically, was doable,” said Vosti. “You can inject lots of micronutrients in bouillon cubes.”

While it was technically possible to produce nutrient-packed cubes, would people actually like them? The UC Davis team worked with researchers at the University of Ghana, including UC Davis alum Seth Adu-Afarwuah, Ph.D. ’06, to determine acceptability prior to a clinical trial. Ghanaian women, recruited by the team, participated in a blind taste test of cubes with and without fortificants and also took samples home to cook with. Despite slight differences in the color of the fortified cubes, the taste testers reported liking all cube formulations.

Testing fortified cubes

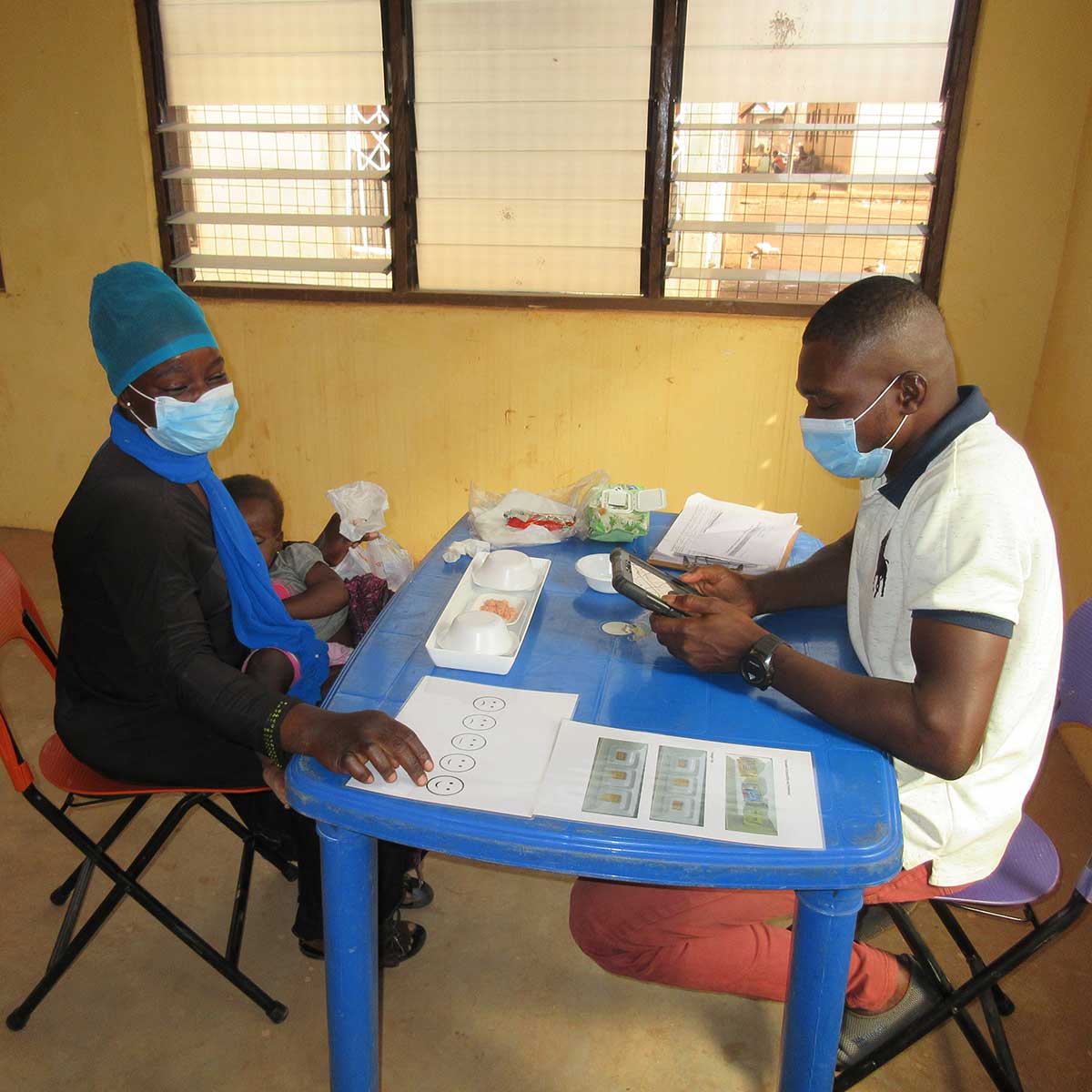

With their cubes ready and approved by the community, the researchers had the green light for moving forward with a clinical trial. In 2023, a field team — which included Davis and UC Davis assistant project scientist Sika Kumordzie as well as University of Ghana collaborators — fanned out across rural and urban neighborhoods in northern Ghana and enlisted a sample of more than 1,000 women and children to participate in the study. Children and pregnant women are most vulnerable to deficiency because they have higher nutrient needs relative to their body weight.

At the start of the nine-month trial, the participants answered questions on income, food and water insecurity, what foods they purchase and eat, their health history, and more. Then they visited mobile labs, where researchers drew baseline blood samples and, from lactating women, breastmilk samples.

Then, the intervention proceeded. Every two weeks, the field team dropped off bouillon cubes, with some participants receiving fortified cubes and others containing only iodine added. Five times across the trial, the team went to the participants’ homes and asked them to recall everything they ate or drank in the previous 24 hours — data that will help researchers home in on relationships between diets and nutrition status. At the end of the trial, participants provided another set of blood samples and — for lactating women — breast milk samples.

Now, the team is analyzing the samples to determine the impact of the fortified cubes. While they have yet to publish their findings, “some of the results that we have seen are very promising,” said Vosti, including a significant increase in vitamin B12 in breastmilk in women receiving fortified cubes.

Modelling nutrition gaps

Alongside the clinical trial, UC Davis researchers also used data on household consumption to build a computer model to estimate the prevalence of dietary micronutrient inadequacies and the potential impact of bouillon fortification. Called the Micronutrient Intervention Modelling Project or MINIMOD, the model focused on the populations of Nigeria, Senegal and Burkina Faso.

Across several papers published together last year in Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, the team reported their findings on dietary adequacy across the three countries. In Nigeria, which has the greatest population of three, the model estimated that vitamin B12 inadequacy of baseline diets in women and children in poorer households was over 65 percent.

The team also found fortifying bouillon cubes with vitamin A, zinc and folic acid — in addition to existing fortification programs — could save the lives of more than 18,000 children under 5 in the country every year; by 2030, fortification could save the lives of more than 57,000 children. “When bouillon fortification is combined with existing large-scale food fortification programs in Nigeria, it may have the potential to virtually eliminate several micronutrient inadequacies,” said Katie Adams, a UC Davis assistant researcher in nutrition and lead author of the findings.

Bringing fortified bouillon to households

With evidence of the benefits of fortifying bouillon growing, including the MINIMOD results, Nigerian officials adopted the new voluntary standards. Now, when companies manufacture bouillon cubes containing 15 percent or more of the recommended daily amount of four nutrients per serving (vitamin A wasn’t included in the standards), they can label the bouillon as a “good source” of those vitamins and minerals. The regulation basically states, as Vosti put it, “If you are going to fortify at all, you must fortify this way.”

While the standards are currently voluntary, Vosti sees them as a stepping stone toward mandatory fortification. For now, companies have time to sort out the technical and commercial details of bringing fortified cubes to markets. The standards may be revised as more information, such as the results of the clinical trial, becomes available. The trial may show, for example, that certain nutrients are not well-absorbed and therefore not cost-effective to include in bouillon.

“The big question will be who covers the costs,” said Engle-Stone. Ideally, companies can absorb some of the extra cost of adding nutrients to avoid passing on that cost to low-income consumers. “People might consume less of it if it’s more expensive,” she said, “which would kind of defeat the purpose.”

Still, the researchers are hopeful the bouillon will provide widespread benefit, perhaps even outside of Nigeria. Other West African countries import products from Nigeria, which has the largest economy in the region and hosts manufacturing plants owned by large food companies, including Nestlé and Unilever (the two companies, among others, are members of the bouillon consortium led by the Gates Foundation). It’s likely that the fortified cubes will filter outward.

The team also hopes the clinical trial will propel wider adoption of fortification, ultimately making a dent in deficiency rates across the region. “I think the ultimate great outcome for this research would be for the results to be used in discussions around a national bouillon fortification strategy within Ghana, and within other countries in West Africa,” said Engle-Stone. “If fortification is adopted, researchers can test again in a few more years and see how micronutrient status is doing, and ideally it would be getting better.”

“We have the potential to save tens of thousands of lives every year with fortification of bouillon,” added Vosti. “That alone is enough for me to advocate for bouillon fortification.”