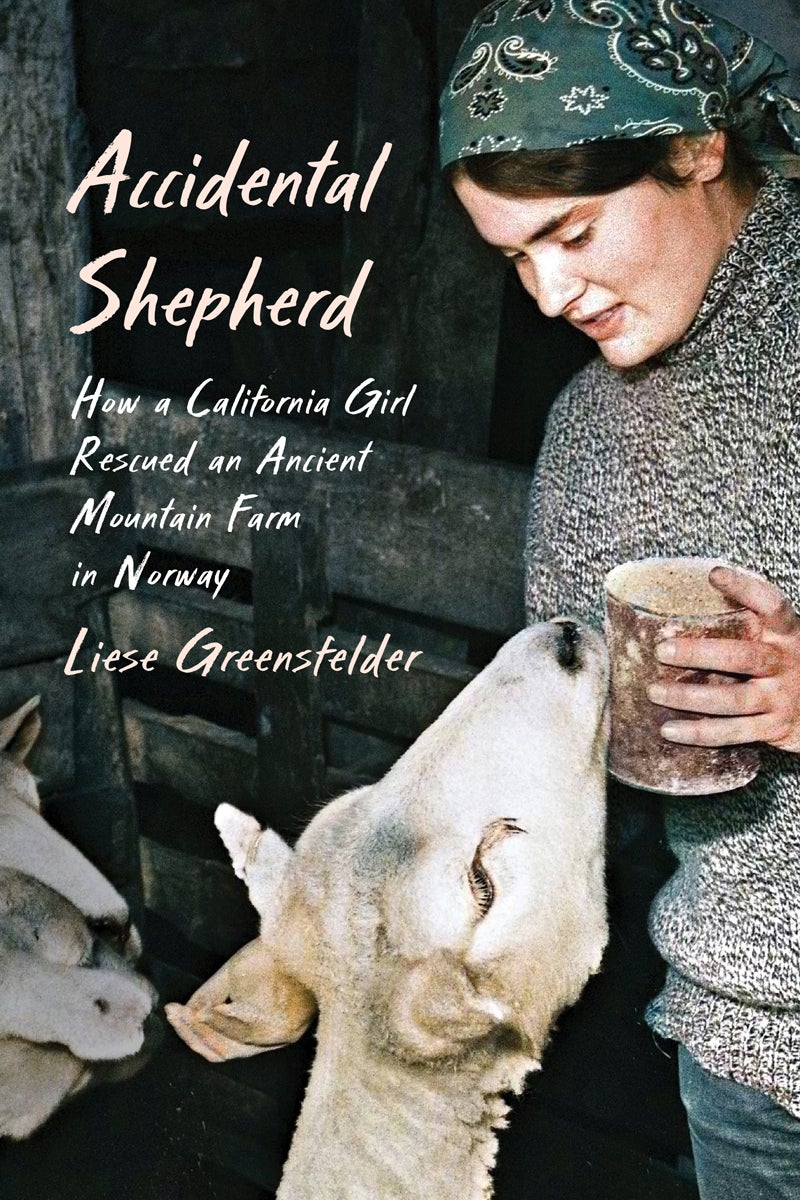

When Liese Greensfelder ’77, M.S. ’83, visits Norway again this summer, the trip will further deepen a bond with the country that goes back decades. When she was 20, Greensfelder temporarily became the sole farmer on a remote Norwegian farm, an experience she describes in a new book Accidental Shephard: How a California Girl Rescued an Ancient Mountain Farm in Norway (University of Minnesota, 2025).

Greensfelder grew up in Mill Valley and after high school spent a year studying in Denmark. In 1972, she signed up to work a summer in Norway.

“I really wanted to go out into the world and get agricultural experience, hands-on farming experience, because I wanted to be a farm adviser in developing countries when I grew up,” she said. “I eventually found this farm to work on.”

When she landed in Norway, however, she discovered the farm owner was hospitalized after a stroke and needed help until he could return. She agreed to stay, taking on 115 sheep, two cows, a calf, a draft horse and a herding dog. The summer job stretched into a year.

Since then, she has been back to Norway several times and remained close to the families she met there. Back in the U.S., she studied at UC Davis, eventually becoming a farm advisor for the University of California Cooperative Extension. She is currently a freelance science writer and editor.

Here, she talks about that year in Norway, finding fame, and how UC Davis became her next stop.

Why did you want to revisit this experience for a book?

The experience has lived with me very strongly my entire life, and it was an amazing experience. I had to get it all down on paper. I also really wanted to show how my neighbors were living and how much they cared for the land and how much they helped me. In a way, it was a way of thanking them. Because I obviously could not have gotten through the year without them. We became just very good friends. And I also hope that it would maybe inspire other people — women — to do something adventurous.

You had an earlier brush with fame at the time, when the Norwegian media told your story. What was that like?

I was on a television show in Norway back when it only had maybe six hours a week of entertainment TV. Everybody watched. Apparently, I made an impression. The farm was flooded with journalists. I was on the cover of magazines, and there were big stories about me in newspapers across the country.

I would be lying to say there wasn't this amazing feeling of pride and excitement, astonishment and just kind of fun being in that position. But I still had to shovel manure every day to take care of the animals and shovel snow. And it was funny thinking, “Well, I'm a celebrity and I'm just covered in manure again.”

That experience led to a book deal to publish your letters from that time. How did those letters help you write this book?

[The experience] has pretty well been sealed in my mind over all these years. But the letters absolutely filled in a lot of the details because I wrote long, detailed letters every week on to my family, mainly my mother, who would have freaked out if she didn't get a letter every week. And so that really helped me. The emotional things, which are still in my mind, I can write about them because they were [so memorable]. But the little details came out in my letters.

What did your parents think about you being out there at such a young age?

There was one letter that my mother wrote to me when she had not heard from me for two weeks, and she was really angry and upset because she was so frightened. She was constantly waiting for letters. But on the other hand, they pretty much raised us to be independent, and all of us really were. I had hoped that they would come and visit me, because I wanted to share that place with them so badly. But it was so expensive, and we were not a rich family. But I know my mom wanted me to come home in the winter because it was dangerous. And she knew by then that the man I was working for had serious mental problems.

I don't want to give away the ending, but the man who owned the farm wasn't very nice. How did you want to approach that aspect of the story?

I wanted to go back there. Before I submitted to agents and then eventually University of Minnesota Press, I asked a professional editor to take a look at it. [I had detailed] two or three really bad episodes — not that he did things to me, but other people that I talk about. And she said, “Liese, this book is not about him. It's about you. We know he's a bad guy. You don't have to tell this story.” And I thought, “Okay, but I want the world to know how bad it was, because it was really hard.” But I think she was right.

How did you land at UC Davis after this experience in Norway?

I just thought, “Wow, I don't know if I can go on to two or three more years of working on farms around the world.” What I really wanted was to get out there and become a professional working for the United Nations. That meant going back to college. I knew I'd have to do that at some point.

At UC Davis, I was a really serious student, and, my friends and I, we all expected to get straight A's and pretty much we did. Then I met my husband-to-be, and after that I was devoting all my free time between coming up to where he lived in Nevada County on the weekends.

But Davis was kind of my second home when I was there as a student and then during the four years I was at Cooperative Extension. I feel very, very close to Davis.