Growers often harvest tomatoes before they ripen in hopes of extending shelf life and avoiding crop loss. But that act of removing the fruit from the vine affects flavor. And storing tomatoes below certain temperatures also hurts quality and shelf life.

New research published this month out of University of California, Davis, examined changes in tomatoes at the molecular level to better understand what happens during postharvest handling and cold storage.

The findings, published in the journal Horticulture Research, are a first step toward establishing optimal tomato handling and storage guidelines and could reduce food loss and waste, said Diane M. Beckles, the senior author on the research and a professor in the Department of Plant Sciences.

“Growers need the flexibility of being able to harvest fruit at different times to maximize profitability,” Beckles said. “We want to extend shelf life but lose as little quality as possible. Looking at how these processes are regulated at multiple levels – including changes in the activity of genes and connecting them to processes that are important to quality – is key to a better understanding.”

Beckles likens the processes in a vine-ripened fruit to an orchestra creating beautiful music under different conductors, each with impeccable timing. “When you harvest early or store at low temperatures, you interfere with the conductors, ruin the tempo and the fruit is not enjoyable,” she said.

Her work is intended to understand the maestros and the conditions and activities that control their timing.

The sweet temperature spot

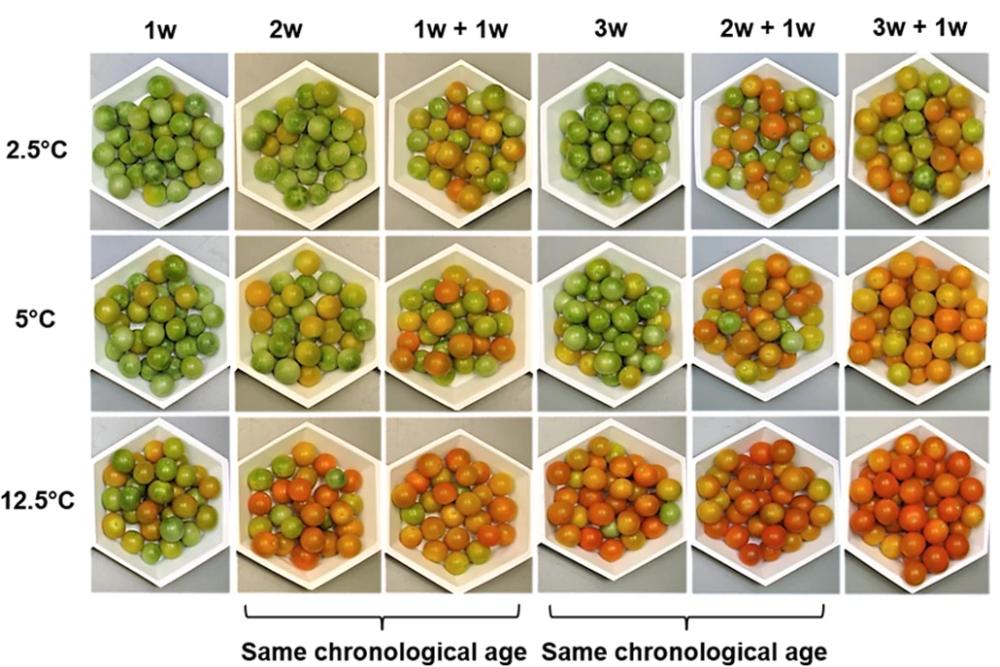

To do the research, the scientists monitored differences in hormones, DNA makeup, gene expression and other biological activities when the fruit were stored at different temperatures, said Jiaqi Zhou, the lead author on the paper and doctoral candidate in horticulture and agronomy.

“We’re trying to understand why the quality is different between the postharvest and the fresh harvest fruit using molecular biology approaches,” Zhou said.

Postharvest fruit refers to fruit that undergo various handling processes, such as early harvesting and low-temperature storage.

Researchers examined unripened green fruit warmed to room temperature after being stored at 41 degrees, 54.5 degrees and 68 degrees Fahrenheit. Storage at 41 degrees led to poor fruit quality but the longest storage time, while the fruit quality at 68 degrees was good but had a shorter storage time. At 54.5 degrees the fruit had acceptable quality and a moderately long shelf-life.

Two things surprised the team: The fruit stored at 54.5 degrees differed most in the timing of biological processes among stored fruit. “At this temperature, the maestros and the processes they regulate were most out-of-sync,” Beckles explained. “We believe that this massive reorganization of the ‘orchestra’ allowed the fruit to adapt to this low but safe temperature during an extended storage.”

Also, early harvest followed by storage in a dark place, which deprives the fruit of full exposure to sunlight, affected how genes were regulated and expressed more than temperature.

Improving practices

This information could be key to maintaining flavor and taste and improve postharvest practices plus inform efforts to modify genes to avoid quality loss.

“Understanding what's happening at the molecular level can provide the fundamental knowledge needed to develop optimal storage, optimal time-of-harvest and perhaps even influence the development of new varieties,” Beckles said.

The importance of photosynthesis – the conversion of sunlight into fuel – in harvested and stored fruit was also investigated. “Our work also suggests that light could contribute to quality,” she said. “Plants use light to make food and energy, therefore exposing cold-stored fruit to light may help to maintain some quality processes typically lost due to cold.”

Preventing loss and waste

The need to reduce loss is there, Beckles said, because 30% of harvested fruits and veggies worldwide are never eaten due to damage, spoiling or appearance.

“This is absolutely unacceptable, given nutritional insecurity and the difficulty in successfully growing crops in the face of climate change,” she said. “Any research that helps us to understand shelf life and qualities is important in helping to reduce the percentage of fruit that would potentially be lost or wasted.”

UC Davis graduates Sitian Zhou, who is now at Columbia University; Bixuan Chen, was at Germains Seed Technology; and Karin Albornoz, who is now an Assistant Professor at Clemson University, contributed to the research, as did scientists Kamonwan Sangsoy and Kietsuda Luengwilai from Kasetsart University in Thailand.

The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Henry A. Jastro Graduate Research awards and the Ministry of Higher Education in Thailand.

Media Resources

Read the paper