As a child in southern India, Rao Vemuri didn't know what the huge lakeside cisterns he and his friends played and swam in were. Later, he learned they were the remains of an indigo factory that extracted the dye from plants by steeping it with cow dung. India once held a lucrative monopoly on indigo but the industry collapsed early in the 20th century when German chemists learned how to make the blue dye artificially.

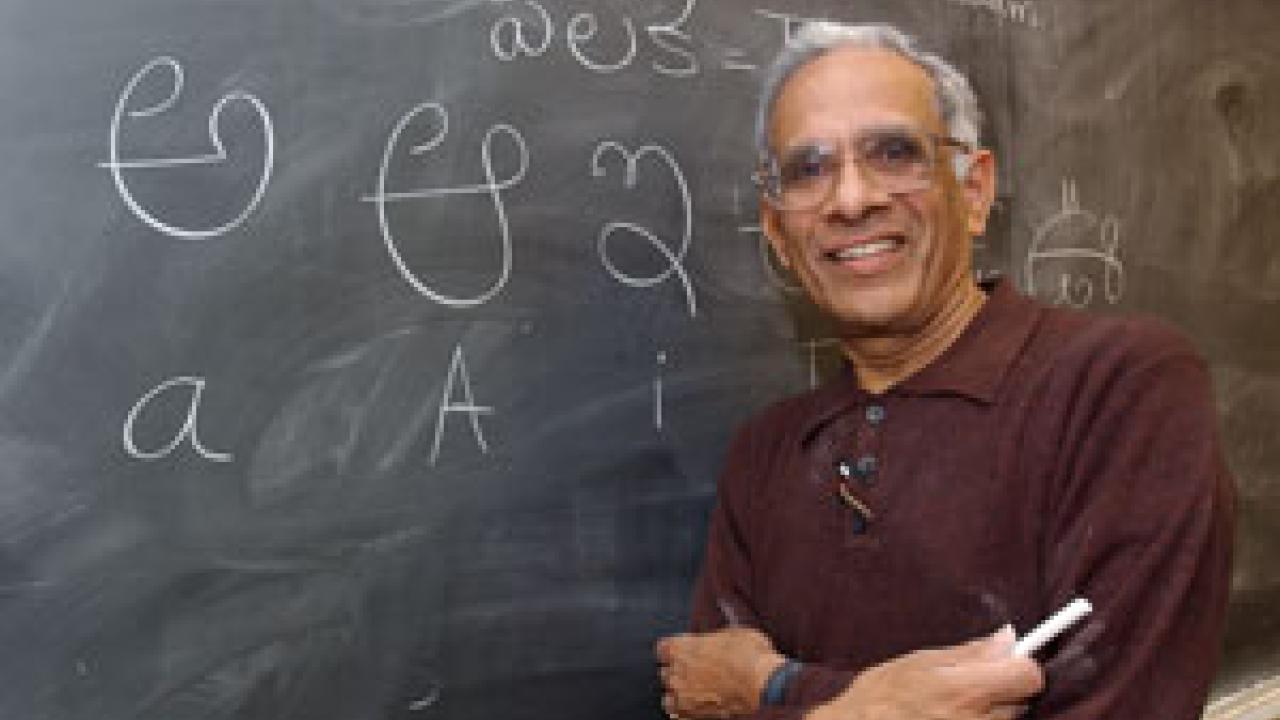

That story combines several themes -- technology and change, tradition and science, globalization and local action -- that run through Vemuri's career. Now a professor of applied science at UC Davis, he's a computer scientist and engineer whose work embraces ideas from biology and medicine; an author of popular science books and science fiction in his native language, Telugu; a lexicographer who has published an English-Telugu dictionary; and founder of a non-profit organization that aims to empower people to solve their problems through education, technology and traditional knowledge.

Telugu is the second-largest of India's 16 main languages, spoken by some 80 million people. When he went to engineering college, where the language of instruction was English, Vemuri realized how much scientific and technical information was available to English speakers but not to the other 99 percent of Indians.

He wrote his first book in Telugu, a primer on computers, as a graduate student at UCLA in the late 1960s. It was later published as a serial in a Telugu magazine. He went on to write a book on the chemistry of household items and everyday life and most recently a book on the blood and circulation, as well as numerous popular science articles, short stories and essays in Telugu.

Because Telugu lacked words for scientific terms, Vemuri both translated English words directly into Telugu and created new Telugu words. In fact, some scientific words in English don't make a lot of sense, but have become accepted by use. For example, "chromosome" derives from the Greek for "colored body" -- a term created by microscopists that has nothing to do with genetics or heredity.

Vemuri said that in his popular science writing, he often finds himself explaining how such words are created. Much of science is about naming and classification, he said.

Commonalities offer a bridge

While English and Telugu look a lot different, their ancestral languages -- Latin and Sanskrit -- share the same ancient roots, and many scientific terms can be traced back to those roots. For example, ancient Indian astronomers used the Sanskrit word "Jiva," meaning "life," to describe angles and curves. Arab scholars studying mathematics in India brought the word to the West, where Europeans in turn translated the term into words equivalent to "curvaceous" and "sinuous," to end up with the terms "sine" and "cosine."

The title of Vemuri's 2002 book on the blood, Jiva Nadi translates approximately as River of Life or The River that Never Dries Up, a play on the close relationship between rivers and life in Indian language and culture.

As a trained engineer, Vemuri said he found learning about the blood a near-religious experience. "Computers and jet engines are nothing compared to biological systems," he said.

His academic research in computing and artificial intelligence draws heavily on biological metaphors to solve problems: neural nets that mimic the connections in a simple brain, genetic algorithms that "evolve" towards a solution, or computer security systems based on how the immune system fends off real-life viruses.

For decades, Vemuri has collected word definitions on filing cards, moving them to a computer as fonts that could display the Telugu alphabet became available. At the urging of friends, he developed his collected glossaries into a two-volume English-Telugu/Telugu-English dictionary, published in 2002. He also teaches a freshman seminar in Telugu language and culture.

A tradition favoring the humanities

A religious and philosophical bent has always been more prominent than science in Indian culture, Vemuri said. India has a scientific heritage that goes back more than 5,000 years to the Vedas. While Vedic writings on subjects such as astrology may not seem very scientific today, the writers were trying to solve the question, "Given these facts I can observe, what will happen tomorrow?" he said.

"Indians tend to be more interested in philosophy, history, 'where do we come from?' questions rather than science," he said. But Vemuri doesn't see any problems for India moving ahead in the technological sphere. Many Indians seem able to reconcile high levels of technology and scientific knowledge with ancient beliefs and religious practices. Perhaps of more concern is that industries that are successful today, such as software, could be gone tomorrow, lost to technological change or competition like the indigo industry.

"Software is similar to indigo, it's a bubble that can burst at any time," Vemuri said.

Six years ago, Vemuri started the ECO Foundation to protect biodiversity and empower people through effective use of traditional knowledge. The foundation has given small grants to conduct workshops, send Indian high school students on field trips, carry out tree plantings and support college students.

Traditional knowledge about plants represents a tremendous resource in India but much of that knowledge has been lost in just a few generations, he said. Ayurvedic texts list medicinal plants but do not give enough information to identify them. The foundation is funding a catalog of plants found on the campus of the University of Hyderabad. When plants are properly identified, their medicinal properties can be explored.

"Whatever I'm doing is miniscule, but you do what you can," Vemuri said.

Media Resources

Andy Fell, Research news (emphasis: biological and physical sciences, and engineering), 530-752-4533, ahfell@ucdavis.edu