A UC Davis and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory team has developed a powerful computing tool that allows scientists to extract features and patterns from enormously large and complex sets of raw data. The algorithm is compact enough to run on computers with as little as two gigabytes of memory.

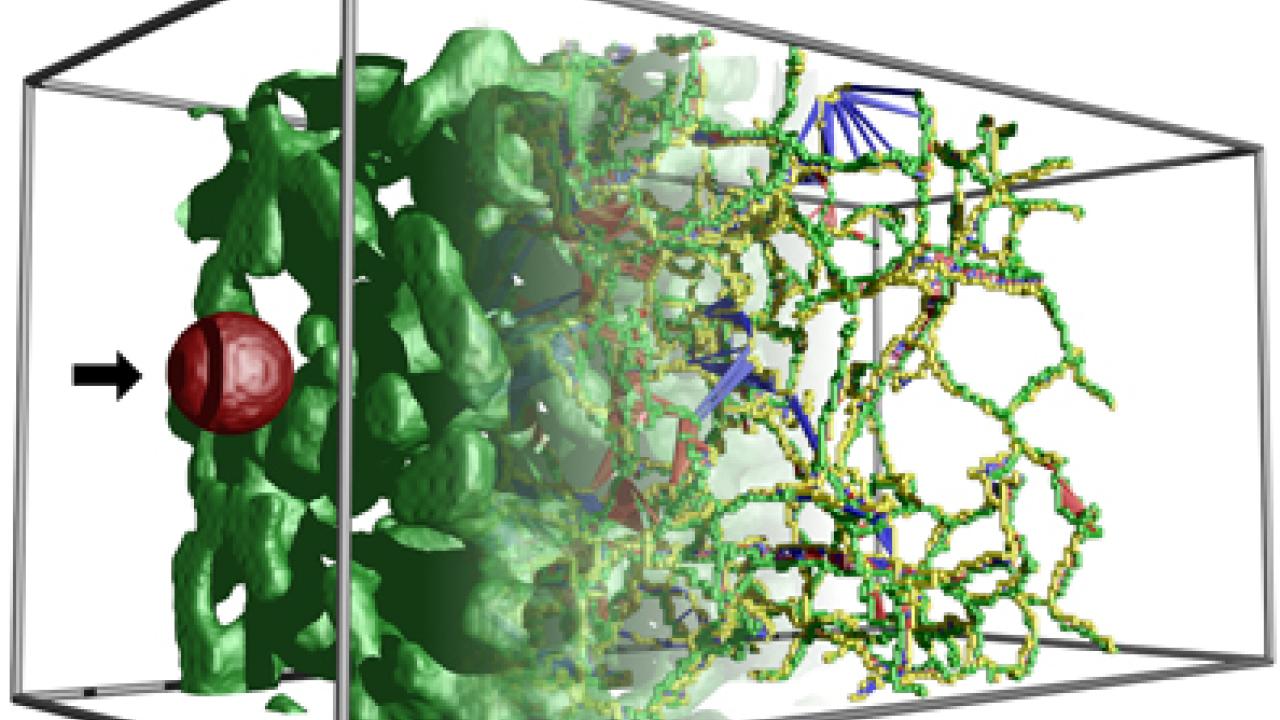

The developers already have used the algorithm to probe a slew of phenomena

represented by billions of data points, including analyzing and creating images of flame surfaces; searching for clusters and voids in a virtual universe experiment; and identifying and tracking pockets of fluid in a simulated mixing of two fluids.

“What we’ve developed is a workable system of handling any data in any dimension,” said Attila Gyulassy, who led the five-year project while pursuing a Ph.D. in computer science at UC Davis. “We expect this algorithm will become an integral part of a scientist’s toolbox to answer questions about data.”

A paper describing the algorithm was published in the November-December issue of IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics.

Co-author Bernd Hamann, a professor of computer science and associate vice chancellor for research at UC Davis, said: “Our data files are becoming larger and larger, while the scientist has less and less time to understand them.

“But what are the data good for if we don’t have the means of applying mathematically sound and computationally efficient computer analysis tools to look for what is captured in them?”

A mathematical tool to extract and visualize useful features from data sets has existed for nearly 40 years —in theory. Called the Morse-Smale complex, it partitions sets by similarity of features and encodes them into mathematical terms. But working with the Morse-Smale complex is not easy. “It’s a powerful language. But ... using it meaningfully for practical applications is very difficult,” Gyulassy said.

His algorithm divides data sets into parcels of cells, then analyzes each parcel separately using the Morse-Smale complex.

Results of those computations are then merged. As new parcels are created from merged parcels, they are analyzed and merged yet again. At each step, data that do not need to be stored in memory are discarded, drastically reducing the computing power required to run the calculations.

Gyulassy is developing software that will allow others to put the algorithm to use. He expects the learning curve to be steep for this open-source product, “but if you just learn the minimal amount about what a Morse-Smale complex is,” he said, “it will be pretty intuitive.”

Other co-authors: Valerio Pascucci, who was an adjunct professor of computer science at UC Davis and a computer scientist and project leader at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory when he did the work (he is now at University of Utah); and Peer-Timo Bremer, a computer scientist at Lawrence Livermore.

Media Resources

Dave Jones, Dateline, 530-752-6556, dljones@ucdavis.edu