In high school in the 1980s, Flagg Miller — now a religious studies professor at UC Davis and author of a new book about Osama bin Laden — decided to spend a year as a foreign-exchange student before going to college.

He requested Asia or Africa. He ended up in Tunisia, attending a Muslim school, formerly for girls, that only recently had opened to boys. He lived with an Arabic-speaking family.

It was a difficult adjustment for a blond boy from Kansas, but it was transforming. He came to love the Middle East — its fascinating people, culture and language — and would return many times as a student and scholar. On one journey, he even spent a few months atop a camel saddle, an imposing contraption he displays in his faculty office.

Although he majored in English, Miller’s graduate studies led him to become a linguistic anthropologist, gaining a command of the Arabic language that few in the Western world possess.

His future: 1,500 audiocassette tapes

Flash forward to 2003, when colleagues with the Afghan Media Project at Williams College, in Massachusetts, took delivery of 1,500 audiocassette tapes found in Osama bin Laden’s house in Kandahar after the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001.

The FBI already had determined the recordings of poetry, song and conversations of bin Laden and his associates had no national security relevance

When you have 3,000 hours of such tape, in various yet-to-be-identified voices speaking Arabic, who could they call but an Arabic linguist at UC Davis? Miller flew to pick them up.

“So, I get these two dusty boxes of tapes,” Miller recalls with a grin and hint of eye rolling. “It was daunting. I didn’t sleep for three days.”

Tapes became The Audacious Ascetic

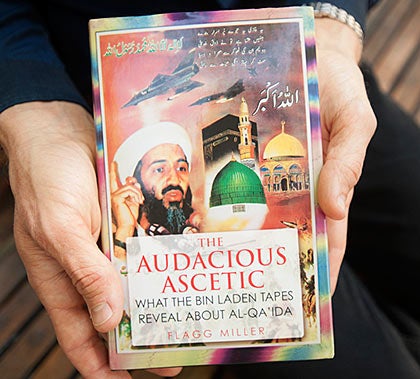

He listened to the jumbled pile of tapes for hours, days and eventually years. Wearing headphones, he transcribed directly from Arabic into English on a laptop. The hand-labeled (and unlabeled) tapes all formed the basis for a book due to be published Oct. 19: The Audacious Ascetic.

“When I started listening, I focused on trying to find bin Laden,” he says. There were more than 200 separate voices in all, and most were not bin Laden, he says.

“After a while, I could identify his voice pretty quickly.”

Bin Laden met his father only five times

He came to know the man, listening to the militant for much more time than bin Laden’s own father had. (Miller says his research indicates bin Laden met his father only five times, for a total time of about an hour.)

The younger bin Laden, a wealthy man from a large family of more than 50 siblings, was slated to be a corporate CEO. He surfaces as someone who wanted more from life — a peripheral player among Islamic militants. He came to occupy central stage by self-marketing, Miller says.

More about Miller and Bin Laden

- Buy the book at UC Davis Stores

- Visit the website for audio recordings and Miller’s translations

- Listen to an August 2015 documentary by BBC

Related story: “What I learned about al Qaeda from analyzing the ‘Bin Laden’ Tapes”

Related story: “A year after bin Laden’s death, professor analyzes his role in 9/11”

Related story: “9/11: Bin Laden’s role exaggerated”

How Al-Qa’ida came to claim 9/11 as its own

In the early years, bin Laden was much more concerned not with the Western enemy of the United States but with disbelieving Muslims who did not adhere to the literal interpretation of Islam — in other words, not the “true Muslims.”

“What people there cared about,” Miller says, “were territories in the Islamic world, not taking over the West.”

Speakers on the tapes begin to learn in the mid-’90s about Al-Qa’ida, which is Arabic for “base” or “rule.” It has different meanings in different contexts.

It is not the militant organization with which people now commonly associate Al-Qa’ida, Miller maintains.

Training camp didn’t connect to bin Laden

The base, in fact, was a specific training camp founded in Afghanistan in the late 1980s for supporting insurgencies within the Islamic world, rather than beyond, and had no significant connection to bin Laden or his ideology, Miller says. It actually was something from which bin Laden was explicity marginalized.

“So how did he manage to steal the limelight and put himself in the center?” Miller asks.

He couldn’t create conditions in his homeland for a revolution, Miller says, “so he had to take on the U.S. or provoke the kind of interventions that happened in Iraq after 9/11.”

There is no foreshadowing or even hint of 9/11 in the tapes.

More Book Talk Stories

Right man to mastermind Al-Qa’ida

But, Miller says, Western intelligence figures found bin Laden to be the right man to be identified as the mastermind of Al-Qa’ida and, eventually, 9/11. “What resulted was a bizarre amalgamation and how bin Laden exploited it.”

Despite the killing of bin Laden and many of his associates, and some historic changes in the region, bin Laden and Al-Qa’ida continue to be identified as players in terrorist activities. This doesn’t surprise Miller.

“When asked six or seven years ago about whether Al-Qa’ida was indeed on its last legs, as reports suggested, I would often reply that it would remain alive and well as long as it could capture headline news,” he says. “And that as long as Arab militants had an anti-American pitch that they could win audiences with under an Al-Qa’ida label, they would claim it as their own.”